The cathedral

It is considered one of Germany’s most beautiful church buildings: the Cathedral of St. Stephen and St. Sixtus in Halberstadt. Built entirely in French Gothic style from the 13th to the 15th centuries, it graces the town with its architectural splendour and the variety of its original furnishings. The 290 images on its stained-glass windows, the altar paintings and the many figural groups offer a vivid impression of mediaeval religious beliefs and artistry. Prominent works such as the baptismal font cut from a block of marble, dating to 1195, or the rood with attendant figures from around 1220 testify to the high aspirations of the donors and artists.

The cathedral was an important spiritual hub in Central Germany; the seat of the bishop and members of the chapter, and a destination for mediaeval pilgrims. Its founding dates back to the times of Charlemagne, in the 9th century. In 1591, the members of the chapter did not fully introduce the Reformation, but decided to retain some aspects of the old faith. Until 1810, Protestant and Catholic clerics worked under one roof. This kept the precious mediaeval works of art preserved in the place they were originally used, with no break in the tradition.

Experience a panoramic tour of the cathedral, created by erlebnisland.de and sponsored by Saxony-Anhalt’s tourism association, LTV.

Experience a 360° tour of the cathedral!

Founding history and first buildings

The Halberstadt diocese and its cathedral date back to Carolingian times. At the start of the 9th century, a Saxon settlement formed near a trade crossroads, centred around a small mission church. A famous document names the emperor Charlemagne (d. 814) as the founder of the diocese, but this is now believed to be a mediaeval forgery. However, there are other written documents testifying to the existence of the Halberstadt diocese in the first half of the 9th century. In 859, the fourth bishop of Halberstadt, Hildegrim II, officially consecrated the first large cathedral, already measuring the impressive length of 74 metres.

In 965, the building collapsed. This was a time that was already difficult for the Halberstadt diocese, when Emperor Otto I elevated Magdeburg to the position of an archbishopric. Halberstadt suffered losses of power and land and went into persisting competition with Magdeburg.

In view of this, work began in Halberstadt on a magnificent new building – 82 metres long and boasting a new westwork on one side and, on the other, an annular crypt and a cross-shaped chapel. After almost 30 years of construction, Bishop Hildeward consecrated the cathedral in the presence of Emperor Otto III, with eleven other archbishops and bishops. In 980, the bishop had brought the relics of St. Stephen to Halberstadt from Metz. The saint had been venerated as the cathedral’s patron since the 9th century. The consecration in 992 meant that St. Sixtus joined Stephen as the cathedral’s second patron saint, enabling another important set of relics to be brought in from Rome.

Three years previously, a charter by Emperor Otto III had granted the burgeoning town of Halberstadt the right to hold markets, mint coins and levy tolls. Soon, it was among the economically most important cities of the empire.

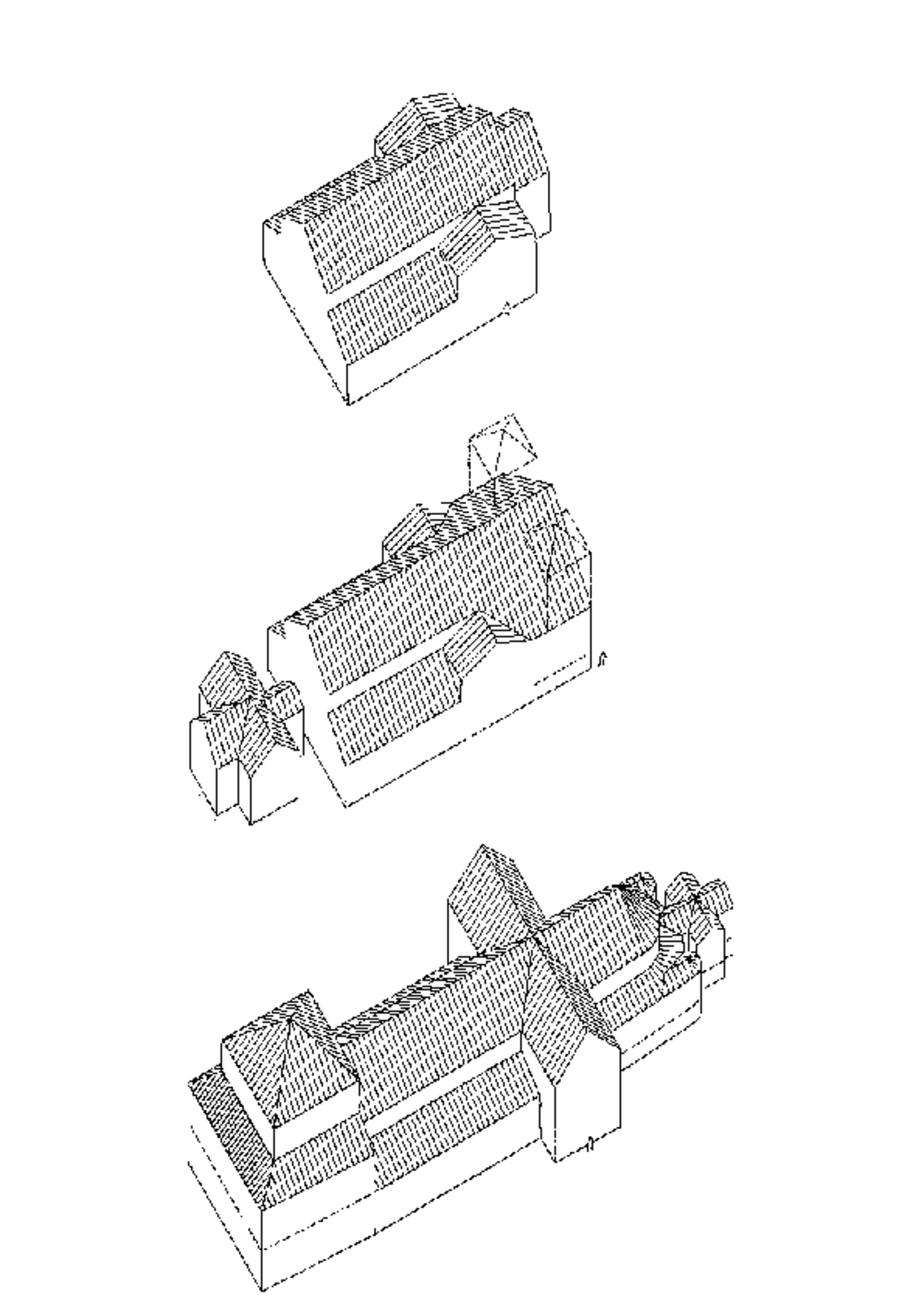

Rekonstruktion der Vorgängerbauten nach G. Leopold 1984

Events of the 11th and 12th centuries

The organisational structures of the clergy at the cathedral continued to take shape into the 11th century. In an attempt to develop a regulated common life in accordance with the Rule of Aix, they constituted a collegiate church. The Rule of Aix allowed them to hold property of their own and of the church. As a result, the canons from wealthy, aristocratic Saxon families no longer lived the monastic common life, but preferred to lodge in their own, grand houses around the cathedral. At the end of the 12th century their number was fixed at 22 canons. These were joined by 30 low-ranking curates who probably lived in the cathedral outbuildings. Of these, the old chapter house has been preserved from Romanesque times. The clergy took part in the hourly prayers and daily Masses, and undertook a wide range of administrative tasks for the diocese. The high number of officials is still reflected today in the choir stalls, with sixty-four 15th-century seats in two rows.

Both the diocese and the town developed into one of the empire’s most important centres. In the 11th and 12th centuries, however, it suffered two waves of destruction. In the 11th century, a fire severely damaged the cathedral, and it took until 1070 to rebuild. A century later, another major catastrophe hit when Halberstadt was besieged and set on fire by Henry the Lion during political conflicts in the Saxon War. The destruction was so devastating that it was hotly debated and censured by contemporaries.

Most of the cathedral was rebuilt by the end of the century. In 1195, Bishop Gardolf von Harbke donated the Romanesque font which is still in use today. The cathedral was officially consecrated after the vaulting was completed in 1220. That is the time when the monumental rood with its attendant figures was built, as still found in today’s Gothic cathedral.

Shortly before, Bishop Konrad von Krosigk had brought a significant set of relics to Halberstadt from Constantinople and the Holy Land, collected on his travels during the Fourth Crusade. Its donation in 1208 was a valuable addition for the local diocese.

The Gothic cathedral

Scarcely 20 years after the Romanesque cathedral was consecrated – probably in 1236, at the latest in 1239 – construction began on a completely new building: today’s Gothic cathedral. This may have been in response to the status-boosting relics which arrived from Constantinople in 1205: the many new relics meant they required a suitable place to house them, as well as means of impressing high numbers of pilgrims. The people of Halberstadt may also have been under pressure to compete with Magdeburg, as construction had already started on a Gothic cathedral there in 1209.

However, political and financial difficulties in the centuries that followed led to the construction work dragging on for some 250 years, throughout the entire Gothic period. To ensure that services could still be held without a break, for a long time, work was carried out around the previous Romanesque cathedral. The first step was the western façade and the three early Gothic bays connecting to it.

The next stage moved on to the opposing, eastern side, where the Chapel of St. Mary the Virgin was built. With figural decorations and stained-glass windows, it dates to the middle of the 14th century, placing it in the High Gothic period. The ambulatory and main choir followed by 1401, and the numerous sculptures of the apostles and patron saints were created in the course of the 15th century. That is also the time at which the two nave aisles were built, while the late Gothic transept with its elaborate stellar vaulting was completed in the 1470s. The last section to be constructed was the central nave; the final vault was completed in 1486.

Gradually, the altars from the previous building were replaced with or supplemented by new ones. Altogether, there were thirty-three. Sculptures continued to be erected until the beginning of the 16th century, while the interior architecture was rounded off by the delicate rood screen c. 1510.

In 1479, the Halberstadt diocese lost its independence; until 1566, it was a suffragan diocese under the authority of the Magdeburg Archbishops, who at the same time acted as the bishops of Halberstadt. Thus, in 1491, it was Archbishop Ernst of Saxony who consecrated the new cathedral in the form presented to today’s visitors. More than 100 metres long, the cathedral consists in a three-naved basilica with a transept, an elongated ambulatory choir and a western façade with two steeples.

After the Reformation

During the decades that followed, a small number of buildings were added to the complex surrounding the Gothic cathedral. At the start of the 16th century, the completed cathedral was supplemented by the small Chapel of St. Mary the Virgin, by the western cloister. This is usually known as the “Neuenstadt Chapel” after Provost Balthasar von Neuenstadt, who donated it. The building and its furnishings, with huge tapestries, a wheel chandelier and an impressive retable behind the altar, testify to his wealth and piety.

At roughly the same time, and until about 1514, work was carried out on what was called the “new” chapter house, extending from the southern gallery to the western building and today holding parts of the exhibition on the cathedral treasures.

After 1591, when Bishop Heinrich Julius introduced the Lutheran teachings, the cathedral chapter remained interdenominational, and stayed that way until it was dissolved in 1810. The joint work by the Protestant and Catholic canons was characterised by tolerance and compromise; a revised order of worship issued in 1591 combined elements of the Catholic rite with the new Protestant ceremony, enabling people to mark the daily canonical hours together. In 1592, the canons had the modern pulpit built in the main nave of the cathedral.

Following the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the diocese was dissolved and became a principality of Electoral Brandenburg. Nonetheless, the bishopric of the former cathedral continued to exit until it was secularised in 1810. Afterwards, the cathedral became part of Halberstadt’s Lutheran Protestant parish.

Centuries later, the cathedral looks today as it did in mediaeval times. As it was a burial-place for bishops and canons, it has been enhanced by numerous artistically fashioned sepulchres and inscribed commemorative plaques from various epochs. In 1718, these were joined by a High Baroque case for the important organ built by Heinrich Herbst. In the 19th century, the towers had to be renovated twice (1857/61 and 1882/96), giving them their tall, slender appearance.

The cathedral in the 20th century

The Second World War in particular brought with it severe setbacks. During the air raid on Halberstadt in 1945, which destroyed around 80 per cent of the town, the cathedral complex suffered twelve direct hits. These caused considerable damage, although the works of art, including the mediaeval stained-glass windows, had previously been brought to safety and survived the devastating attacks.

As soon as the war ended, the architect Walter Bolze made it his life’s work to rebuild the cathedral, in the face of great difficulties. Piles of rubble had to be cleared, and the project struggled with a lack of money, workers and, especially, materials. The first services were held again in 1956. In the 1960s, the cathedral was given a slate roof.

In 1956, the rood and its attendant figures returned to their place at the cathedral crossing. The renowned stained-glass windows of the Chapel of St. Mary the Virgin and that depicting the legend of John the Evangelist in the south-east cloister were replaced by 1959. The tracery above the window depicting John the Evangelist was filled with new glass windows designed by Charles Crodel. Finally, in 1965, the cathedral organ was installed behind the High Baroque case from 1718: an instrument with 66 stops from the Eule organ-building workshop in Bautzen. Since 2013, the enormous new window in the south transept, based on a design by the Wernigerode glass artist Günther Grohs, has bathed the cathedral in multi-coloured light. Its counterpart in the north transept is currently also being worked on by Grohs.

Since 1996, Kulturstiftung Sachsen‑Anhalt has owned the cathedral and been responsible for the buildings’ conservation and restoration.